Current democratic deficits and proposed solutions

For German: Article-Heilbronn-Fordem-German

Although more than 50 percent of Heilbronn’s residents are immigrants or have at least one parent who is an immigrant, this group is hardly represented in the municipal council. Next year’s local elections will determine whether this democratic deficit will continue. A new organization founded in Heilbronn wants to simplify engagement and co-determination using an innovative digital democracy platform.

Heilbronn is a city of immigration and immigrants, and it has been for decades, if not centuries. Located on the Neckar river, this city has almost always been prosperous. Large and small businesses need plenty of staff, and people from all over the world have made Heilbronn their new home. At the end of 2020, 27.2 percent of Heilbronn residents had a citizenship other than German and another 27.1 percent had German citizenship with “migration background,” as it’s called in Germany, meaning they are naturalized citizens and/or one or both of their parents were born abroad.

In the municipal council, on the other hand, it seems only two members out of 40 have any sort of migration background. The office of the council has confirmed that one member was born in Switzerland. It is further known that another member has a parent who was born abroad. Thus the majority of Heilbronners is hardly represented in this respect in the municipal council. One grows weary of saying it, but in this particular context it bears pointing out explicitly: Heilbronn would not be what it is today – economically, socially, culturally – were it not for the people who arrived here from other countries.

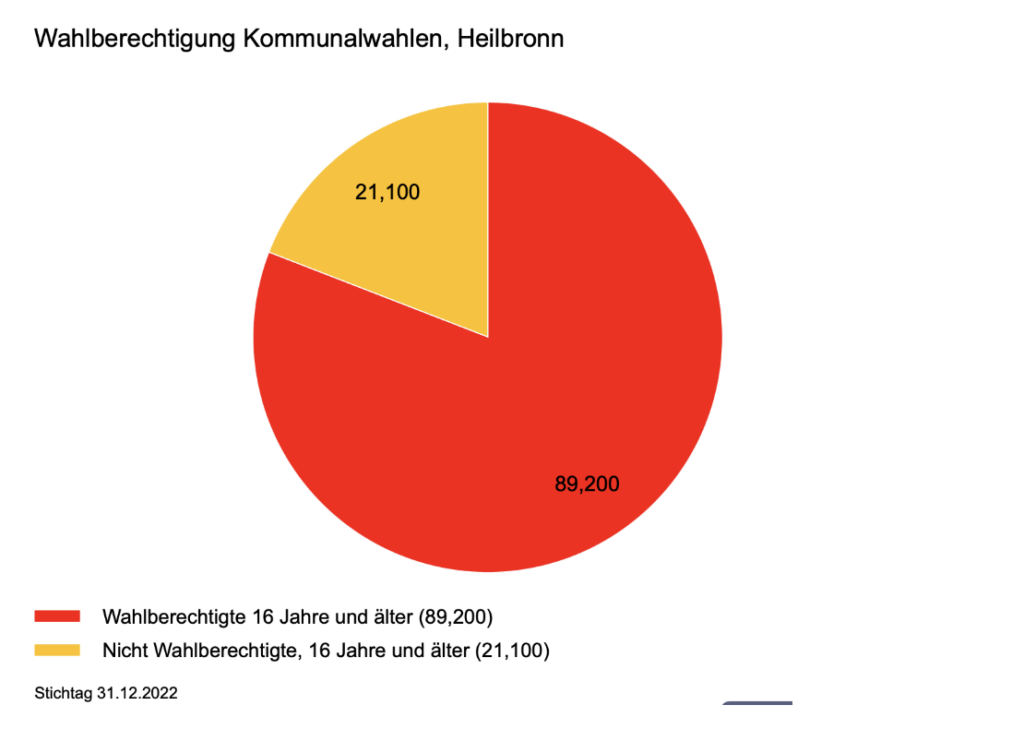

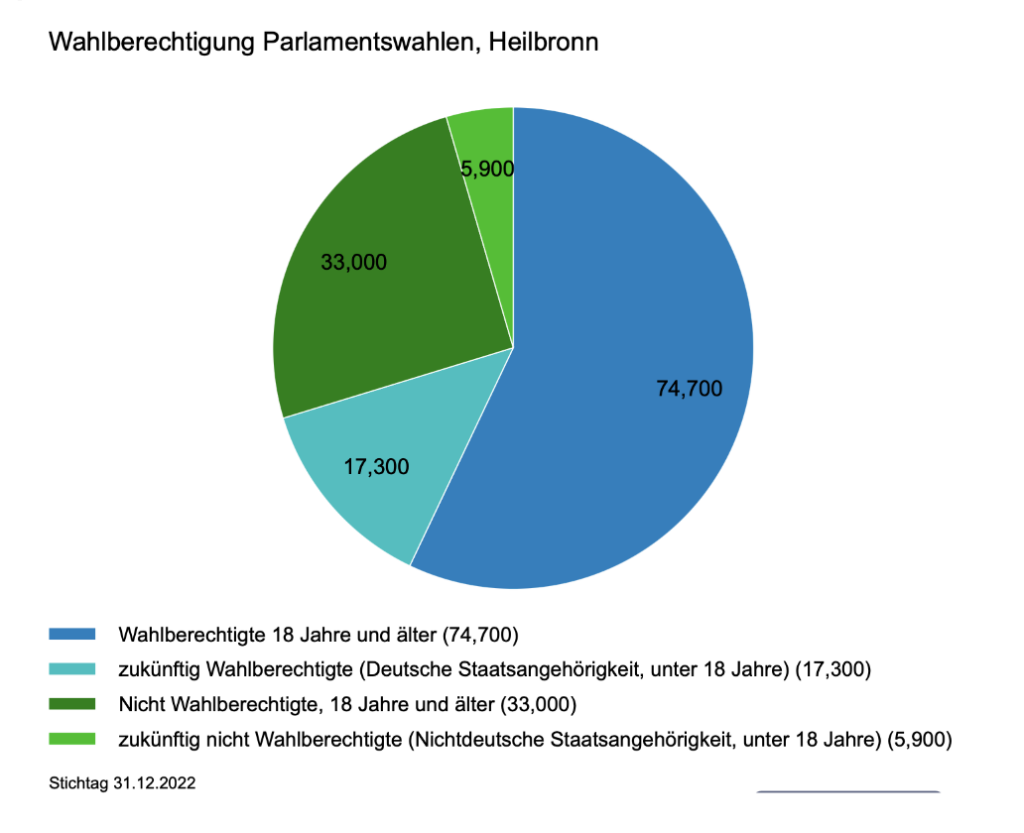

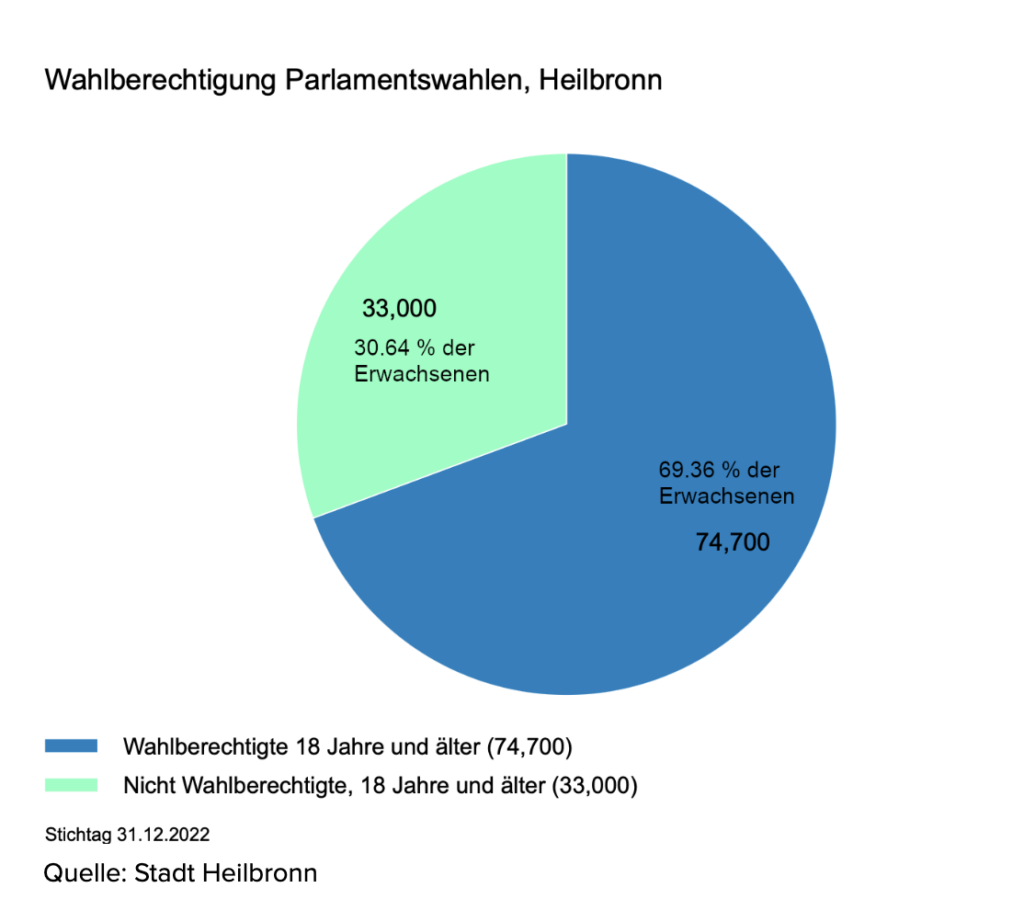

How has this democratic deficit come about? Several factors play a role here. First of all, people who do not have German citizenship are not allowed to vote in federal or state elections. In local elections citizens of other EU member states are allowed to vote but not citizens of third countries. As of December 31, 2018, there were 17,800 people over the age of 16 living in Heilbronn who could not vote in local elections for this reason. That number has increased by 3,300 people to 21,100 within the past four years, which amounts to a share of 19.13 percent of the adult population (16 and older). Those eligible to vote in state and federal elections, with the age requirement of 18 years, numbered 74,700 as of December 31, 2022, compared to 33,000 who were ineligible. This is a share of more than 30 percent of the adult population (18 and older). In addition, there are 5,900 children and young people who, by today’s rules, will not be allowed to vote when they turn 18.

The only way for a non-German to have a vote (except EU citizens, who can vote in local elections) is to become a naturalized citizen. This involves a process that is strewn with hurdles; an astonishing number of documents must be prepared and submitted, and a number of other conditions, rigidly formulated and strictly observed, must be met. The last step – for those who manage to reach it –, in many cases is to give up one’s previous citizenship, forever. Perhaps the reader can better imagine what this might mean using the example of a certain docu-soap currently popular in Germany: How many of the German emigrants, as they are called in the series title, upon moving to Canada, the USA, Thailand or elsewhere, would give up their German passport and all the privileges associated with it—including the possibility of ever returning to Germany, even in old age?

If one also looks into the question of why EU nationals are allowed to vote in local elections even without German citizenship and they are allowed dual citizenship, one can speak of discrimination. Here, citizens with non-European nationalities are obviously granted fewer rights of co-determination. Gülistan Ates lives in Heilbronn and is herself affected since she cannot vote. She describes the situation as follows: “Being politically active, but still not being allowed to vote in local elections, due to the lack of a European passport, shows once again that population groups are marginalized and the mentality of Eurocentrism is deeply rooted in Germany. Living in Germany for 26 years but still not being allowed to vote shows that we are considered second-class people.”

The 33,000 Heilbronners who cannot vote – or 21,100 in local elections – include people who were born here, people who have lived here for decades; people who have businesses, pay taxes and are involved with the society in a variety of ways, and yet are left entirely without a voice in the democratic system and are thus denied the right to help shape democratic processes.

To better understand this special situation in Heilbronn, it is worth taking a closer look at the local elections. When a political party wants to participate in a local election, they first elect a list of candidates within their party. The higher up this list a name appears, the better that candidate’s chances of getting a seat on the municipal council. A good 27 percent of Heilbronn residents have both a migration background and the right to vote – as well as the right to stand for election. The pool of competent, committed citizens with a migration background who could be voted onto the party’s list is therefore not a small one. But it is also important that a candidate receive direct votes. Just being on the list, even in one of the top spots, is not enough to put an individual into office, even if the party does well in the election. The seats won by the party will be awarded to those highest up the list – and groups marginalized elsewhere in society are just as likely to be marginalized when the list is drawn up and when people are casting their direct votes. A similar phenomenon is seen in regard to women in politics; in the case of citizens with a migration background, it is of course also due in part to the 27 percent who are unenfranchised.

The city of Heilbronn has instituted an Office for Participation and Integration – the name itself featuring two of the main topics addressed in this article – and implemented various related measures, such as establishing an integration advisory board and training “cultural mediators” and “welcome guides.” But as the figures noted above show, these offers can do no more than scratch the surface as long as they do not lead to more Heilbronn citizens with migration backgrounds sitting on the relevant committees. Without fostering active political participation, such parallel committees can serve only as fig leaves. The Youth Community Council is far more representative – and among the young people of Heilbronn, the proportion of those with a migration background is even higher – but again, this has not led to more representation on the city council.

What can be done to address this democratic deficit? There is another local election next year. The political parties can act now: reach out to members who have migration backgrounds, encourage and help them prepare to stand for election, find new members, and connect with migrant people’s associations. The city’s Office of Participation and Integration can provide support, spread the word to the communities, and build bridges to the political parties. But all this will not be enough to close the gap between the demographics of the city and those of the political structures, which is why new ideas must be found.

Members of the Transnational Community Federation e. V. (TCF), founded in Heilbronn, Germany, are currently developing a new way for all Heilbronners to engage; most importantly, for those who are ineligible to vote. The idea is to use new technologies to facilitate participation, as well as access to and exchange of political information. TCF has initiated a digital democracy project called Fordem (“for democracy”) to create a platform that provides information on local developments and events, with an app as a portal where users can write and respond to polls, network with others to engage in deliberation with existing groups, and get involved, organize and mobilize. The platform will be offered in several languages and formats, creating new opportunities for information exchange, networking, deliberation and participation in a fully open-source and transparent environment. The teams involved in Fordem pay particular attention to issues around privacy and data protection. With Fordem, each user has an individual digital signature and can take part under a pseudonym. In this way, fair surveys can provide a reasonably accurate picture of citizens’ opinions. Fordem is a civic tool offered to society free of charge.

Fordem has the potential to make next year’s local elections more inclusive, and to reach more people with migration backgrounds and win them (for) a place on the list. The platform also offers the possibility to spread decision-making in the councils more broadly and to include opinions and ideas of a large number of citizens, which can strengthen democracy in Heilbronn.

Sources and further information

Information from the City of Heilbronn electoral register

Information about eligible voters in the Heilbronn metropolitan area | ||

| Parliamentary elections (rounded figures) | ||

| (People aged 18 and older with German citizenship are eligible to vote) | ||

| 31.12.2018 | 31.12.2022 | |

| No. of eligible voters aged 18 and up | 77,000 | 74,700 |

| Eligible to vote in the futureGerman citizenship; under age 18 | 17,900 | 17,300 |

| Not eligible to vote, aged 18 and up | 29,700 | 33,000 |

| Not eligible to vote in future(non-German citizenship; under age 18) | 4,000 | 5,900 |

| Local elections (rounded figures): | ||

| NOTE: These figures show only the numbers of “EU-citizens” eligible, and “non–EU-citizens” ineligible, to vote in future. | ||

| In addition to people with German citizenship, citizens of other EU countries are eligible to vote. Voting age begins when the 16th birthday is reached. | ||

| 31.12.2018 | 31.12.2022 | |

| No. of eligible voters aged 16 and up | 91,300 | 89,200 |

| Eligible to vote in the futureGerman citizenship; under age 16 | 17,600 | 17,300 |

| Not eligible to vote, aged 16 and up | 17,800 | 21,100 |

| Not eligible to vote in future (Non-EU citizen, under age 16) | 1,900 | 3,300 |

- https://fordem.org

- https://www.betterplace.org/de/projects/123115?utm_campaign=user_share&utm_medium=ppp_sticky&utm_source=Link

- https://transcf.org

- https://www.heilbronn.de/fileadmin/daten/stadtheilbronn/formulare/leben/heilbronn_entdecken/stadtteile/Einwohnerstatistiken_Heilbronn_und_Stadtteile.pdf

- https://www.heilbronn.de/fileadmin/daten/stadtheilbronn/formulare/rathaus/gemeinderat/Liste_des_GR_mit_E-Mail_Stand_15.07.2022.pdf

- https://www.dw.com/de/wie-h%C3%A4lt-es-europa-mit-dem-doppelpass/a-63927440